Denise said Greg often deflated the buildup with a joke:

“His line always was: ‘Yeah, I just carried Artis’ Gatorade.’

“I hadn’t known anything about the team, but eventually I found out Greg did so much more than that!”

Nelson was part of the most storybook of all Cinderella teams to play in the NCAA Tournament’s championship game.

He was a 6-foot-6 forward on the Jacksonville team that made that improbable 1970 run. At the time JU had just 2,300 students and it remains the smallest school ever to play in the Division title game.

Six seasons earlier Jacksonville’s recruiting budget was just $250 and two seasons before the glorious run, the Dolphins lost to Wilmington College, which came down from Clinton County and won, 75-73.

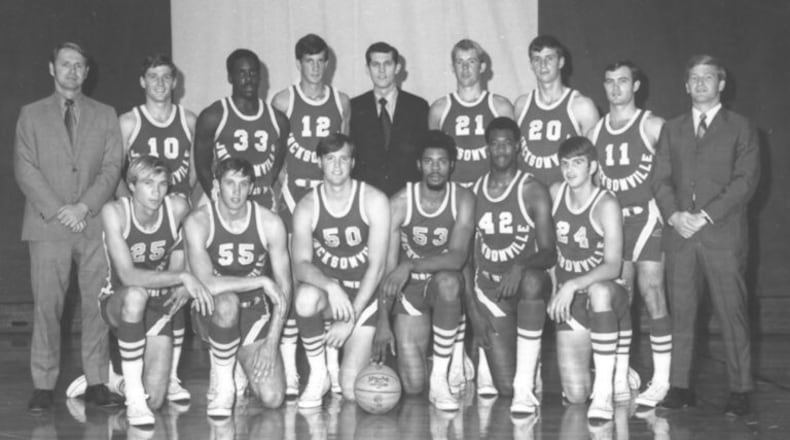

By that 1969-70 season, the Dolphins – with a frontcourt that included the 7-foot-2 Gilmore, 7-foot Pembrook Burrows and 6-foot-10 Rod McIntyre – had the tallest team in Division I.

They were the first team ever to average over 100 points a game (100.4) for a season – this before the three-point line – and they defeated five top 15 teams, including three, No. 7 Iowa, No. 1 Kentucky and No. 3 St. Bonaventure, in the NCAA Tournament.

But like the University of Dayton had three years prior, they fell to UCLA in the national championship game and ended up 27-2

After averaging 12.1 points and 6.8 rebounds a game in his three seasons at Jacksonville, Nelson played professionally in Belgium, served as an FBI agent in Washington D.C, and ended up moving to Dayton in 1978 to work for the Health Care Management Corp, which ran several nursing homes. He became president of the firm and then opened his own company. His last project here was The Carlyle House on Far Hills.

“Greg really loved helping people,” Gilmore said the other day. “When he went into health care, it gave him an opportunity to connect with people and make an impact in their lives.”

Through it all Nelson remained committed to Jacksonville University – he served on the Board of Trustees – and he embraced Fairmont High School, where his four sons and two stepchildren all played sports and where he became a tenacious force that promoted the building of Trent Arena.

On Feb. 4, Nelson – who dealt with heath issues in recent years – died at age 71.

This evening there will be a gala Celebration of Life for him at the Estate at Sunset Farm outside Bellbrook. It will begin at 5 p.m. with drinks, eats and music and end with a big fireworks display – “Greg loved fireworks,” Denise said – put on by Rozzi Fireworks, which does the shows for the Cincinnati Reds and the WEBN Labor Day spectacular.

In between there’ll be a few speakers, including two of his 14 grandchildren and Gilmore, the consensus All American who averaged 26.5 points and a nation-leading 22.8 rebounds a game that 1969-70 season, played professionally for 18 seasons, was an 11-time NBA and ABA All Star and is enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Gilmore will tell you Nelson did far more than “carry” his Gatorade. He was part of a team whose greatest accomplishments weren’t all tallied on the scoreboard. The Dolphins didn’t just beat opponents, they overcame the racial prejudice and restrictions of the time.

“Considering the way the issues were back then, what we did was unique,” Gilmore said. “And because of it, we developed an unusual and extraordinary relationship.”

Jacksonville wasn’t known for tolerance back then as was evidenced by the 1960 Ax Handle Riot at a city park where blacks holding a sit-in to oppose segregation were met by some 200 Ku Klux Klan members swinging ax handles and baseball bats.

Black students who tried to sit at the segregated lunch counters at Woolworths and Morrison’s Cafeteria were denied service, kicked, punched and spat on.

And in 1969, a few weeks before that memorable JU season, a white cigarette salesman shot a 20-year-old black man, then fired into a crowd that included school kids. Buildings ended up set on fire and racial animosities smoldered.

That season the entire Southeastern Conference had only one black player.

Jacksonville had three: guard Chip Dublin, who JU coaches had found working in a bank in New York City, and the original Twin Towers -- Gilmore and Burrows – both unknown junior college transfers.

A year earlier, the Dolphins went to a popular chicken restaurant, where the owner welcomed the team, but told Dublin – then the only black – he’d have to eat in the kitchen.

Head coach Joe Williams stepped in and said then the whole team would eat in the kitchen. The chastened owner relented.

Williams didn’t kowtow to old guard notions in basketball either. His team was called The Mod Squad. The black players had Afros. At games Williams wore his lucky white blazer, blue bellbottoms and a red shirt with a psychedelic tie.

And before games Dublin switched his soul tape to Sweet Georgia Brown, the signature tune of The Harlem Globetrotters, and JU went through a showboat warmup. Although the dunk was then outlawed in college, the Dolphins – before the refs took the floor – often put on a dunking exhibition that included Nelson.

“Basketball is supposed to be fun,” Williams told reporters.

Some sportswriters and coaches took offense, painting the Dolphins as some kind of renegade team.

In truth, they were delivering beautiful lessons for everybody back then.

Some of the players, especially Burrows, shared some thoughts in a superb documentary on the team – “Jacksonville WHO?” – done by television producer and writer Frank Pace, a JU alum.

Burrows noted how black and white players got along, went places together and set a precedent for the city.

Frances Kinne, the former JU president who died last year at 102, noted how the team brought everyone together:

“I had never seen that before and I thought, ‘What a wonderful way to live!’”

‘They made a difference’

Nelson and 5-foot-10 point guard Vaughn Wedeking, his high school teammate in Evansville, Ind., came to Jacksonville together, as a package deal.

Star guard Rex Morgan came from the University of Evansville University and a stint in junior college. Mike Blevins, out of Springboro, had played briefly at the University of Dayton before joining the Dolphins.

Other players had similar odysseys and Williams and assistant Tom Wasdin molded them into a team that lost just one regular season game – to Florida State, who JU beat in the rematch – in the 1969-70 regular season.

The NCAA Tournament run began at UD Arena, where Gilmore scored 30 points and had 19 rebounds in a victory over Western Kentucky.

With Nelson scoring 19 points, the Dolphins then edged Big Ten champion Iowa, 104-103. Next came a 106-100 upset of Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky. The Dolphins then beat St. Bonaventure, playing without injured star Bob Lanier, in the Final Four semifinal.

UCLA, which shot 27 more free throws than did JU, won the title game, 80-69, and gave the Bruins their fourth championship in a row and sixth in seven years.

When they got home the Dolphins were greeted by 10,000 well-wishers at the Gator Bowl.

Alvin Brown, who is black and was the Jacksonville mayor from 2011 to 2015, told Pace the 1970 Dolphins “changed the course history” in the city and paved the way for someone like him:

“They made a difference and they’re still making a difference in the city today.”

A dreamer

Donny Fortener is speaking at today’s celebration, as well.

His son Nick and Greg’s son Sean were multi-sport freshmen athletes in Kettering when tragedy struck another freshman standout in April of 1995.

Bradley Derrickson, who was 16, was struck by lightning as he walked though Oak Creek Park with two other kids and he died a few days later.

“The big thing I remember is Greg hugging every kid he could that weekend at the funeral,” Fortener said. “That really made an impression.”

It was during that time that Nelson became driven by the idea that Fairmont needed a better gym for its kids and the community.

“He looked at the old gym and said, ‘We’re better than this,’” Denise recalled. “I remember he used to walk around with some architect plans under his arm trying to get the community interested.”

Fortener said Nelson eventually connected with Jim Trent, then the head of the school board, and they eventually got a $102-million bond proposal on the ballot and it won.

The first game at the Trent Arena was in 2005.

“Greg was a dreamer,” Fortener said. “He dreamt things and made them happen. Not many people can say that.”

About the Author